合成和生物网片在腹壁重建中的效果:美国疾病控制和预防中心 1 级和 2 级伤口倾向匹配分析。

IF 3.2

2区 医学

Q1 SURGERY

引用次数: 0

摘要

导言:在腹壁重建中,选择生物网片还是合成网片仍存在争议,尤其是在美国疾病控制和预防中心评定的 1 级和 2 级伤口中。本研究通过2:1倾向匹配样本和长期随访评估了伤口并发症和疝气复发情况:我们在前瞻性维护的腹壁重建数据库中查询了在疾病控制和预防中心1级和2级伤口中使用生物或合成网片进行开放式腹壁重建的患者。接受合成网片或生物网片的患者按 2:1 的比例进行倾向评分匹配。进行了单变量、双变量和推理分析。除非另有说明,否则数据均以生物网片与合成网片的比较进行报告:共有 519 例患者进行了比较,其中 173 例使用生物网片,346 例使用合成网片。缺陷大小(215.2 ± 153.6 cm2 vs 251.5 ± 284.3 cm2)、体重指数(33.6 ± 9 kg/m2 vs 34 ± 17.7 kg/m2)和合并症的匹配度很高(P 均大于 0.05)。虽然匹配中使用了美国疾病控制和预防中心的伤口等级,但组间差异显著(美国疾病控制和预防中心 1:43.4% vs 81.2%,美国疾病控制和预防中心 2:56.6% vs 18.8%;P < .001)。组件分离率(40.1% vs 44.2%;P = .397)、筋膜闭合率(97.7% vs 98.3%;P = .738)和脓肿切除率(33.5% vs 29.2%;P = .315)相似。网片大小也相似(816.4 ± 555.5 vs 892.2 ± 487.8 cm2;P = .112)。伤口并发症相同,包括伤口破裂(10.5% vs 7.5%;P = .315)、伤口蜂窝组织炎(5.2% vs 5.8%;P = .843)、伤口感染(7.5% vs 4.6%;P = .223)、需要干预的血清肿(6.4% vs 7.8%;P = .597)和网片感染(1.2% vs 0.9%;P > .999)。生物组的住院时间延长(6.8 ± 5.5 天 vs 5.4 ± 2.3 天;P < .001),住院费用增加(82,181 ± 50,356 美元 vs 62,221 ± 26,817 美元;P < .001)。生物修复术后的平均随访时间更长(33.9 ± 36.6 个月 vs 23.3 ± 32.3 个月;P < .001)。生物组和合成组的疝气复发率差异不大(2.9% vs 1.4%; P = .313)。在多变量回归中,伤口并发症是复发的预测因素,而泛影葡胺切除术是伤口并发症的预测因素:结论:在对美国疾病控制和预防中心 1 级和 2 级伤口进行的 2:1 匹配分析中,在近 3 年的随访中,生物网片和合成网片在腹壁重建中的伤口并发症和复发率相似。本文章由计算机程序翻译,如有差异,请以英文原文为准。

Outcomes of synthetic and biologic mesh in abdominal wall reconstruction: A propensity-matched analysis in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention class 1 and 2 wounds

Introduction

The choice of biologic compared with synthetic mesh in abdominal wall reconstruction remains controversial, especially in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention class 1 and 2 wounds. This study evaluated wound complications and hernia recurrence with a 2:1 propensity-matched sample and extended follow-up.

Methods and Procedures

A prospectively maintained abdominal wall reconstruction database was queried for patients undergoing open abdominal wall reconstruction using biologic or synthetic mesh in Centers for Disease Control and Prevention class 1 and 2 wounds. Patients receiving synthetic or biologic mesh were propensity score matched in a 2:1 fashion. Univariate, bivariate, and inferential analyses were conducted. Unless stated, data are reported as biologic compared with synthetic.

Results

In total, 519 patients were compared, 173 with biologic and 346 with synthetic mesh. Defect size (215.2 ± 153.6 cm2 vs 251.5 ± 284.3 cm2), body mass index (33.6 ± 9 kg/m2 vs 34 ±17.7 kg/m2), and comorbidities were well matched (all P > .05). Although Centers for Disease Control and Prevention wound class was used in the match, it was significantly different between groups (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1:43.4% vs 81.2%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2:56.6% vs 18.8%; P < .001). The rate of component separation (40.1% vs 44.2%; P = .397), fascial closure (97.7% vs 98.3%; P = .738), and panniculectomy (33.5% vs 29.2%; P = .315) were similar. Mesh size was also similar (816.4 ± 555.5 vs 892.2 ± 487.8 cm2; P = .112). Wound complications were equal, including wound breakdown (10.5% vs 7.5%; P = .315), wound cellulitis (5.2% vs 5.8%; P = .843), wound infection (7.5% vs 4.6%; P = .223), seroma requiring intervention (6.4% vs 7.8%; P = .597), and mesh infection (1.2% vs 0.9%; P > .999). The biologic group had an increased length of stay (6.8 ± 5.5 days vs 5.4 ± 2.3 days; P < .001) and greater hospital charges ($82,181 ± 50,356 vs $62,221 ± 26,817 USD; P < .001). Mean follow-up after biologic repair was longer (33.9 ± 36.6 months vs 23.3 ± 32.3 months; P < .001). Hernia recurrence between the biologic and synthetic groups was not significantly different (2.9% vs 1.4%; P = .313). On multivariable regression, wound complications were predictive of recurrence, and panniculectomy was predictive of wound complications.

Conclusion

In a 2:1 matched analysis of Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 1 and 2 wounds with nearly 3-years of follow-up, biologic and synthetic mesh had similar rates of wound complications and recurrence in abdominal wall reconstruction.

求助全文

通过发布文献求助,成功后即可免费获取论文全文。

去求助

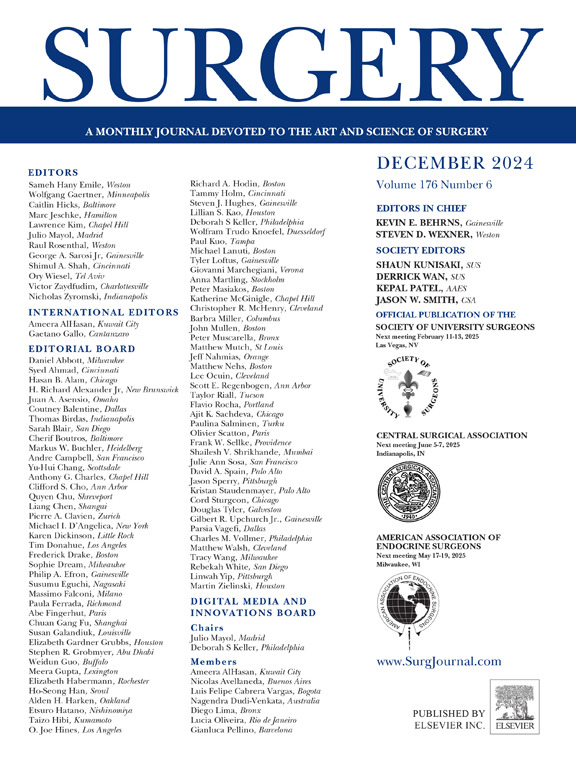

来源期刊

Surgery

医学-外科

CiteScore

5.40

自引率

5.30%

发文量

687

审稿时长

64 days

期刊介绍:

For 66 years, Surgery has published practical, authoritative information about procedures, clinical advances, and major trends shaping general surgery. Each issue features original scientific contributions and clinical reports. Peer-reviewed articles cover topics in oncology, trauma, gastrointestinal, vascular, and transplantation surgery. The journal also publishes papers from the meetings of its sponsoring societies, the Society of University Surgeons, the Central Surgical Association, and the American Association of Endocrine Surgeons.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: