以中心为基础的早期教育干预改善入学准备:系统回顾

摘要

在全球范围内,儿童在法律上有义务在一定年龄(从4岁到7岁)上学。在入学时很少考虑到发展差异,也总是反映在教学环境中。没有做好应对准备就开始上学的儿童可能处于明显的不利地位。学业失败会直接影响长期后果,如失业、犯罪、少女怀孕以及成年后的心理和身体疾病。相比之下,在学校取得成功会对孩子的自尊、行为、态度和未来的成就产生积极的影响。入学准备干预旨在为儿童准备教育的学术内容和被认为对学习很重要的社会心理能力,如自我调节、倾听、听从指示和学习在游戏和其他社会环境中分享。有必要证明以中心为基础的入学准备干预措施的有效性。目的评价以中心为基础的干预措施对改善学龄前儿童入学准备的效果。在2021年10月,我们检索了CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, ERIC, PsycINFO, ERIC,另外8个数据库和3个试验注册库。其他符合条件的研究是通过手工检索参考文献列表、报告、评论和相关网站来确定的。我们纳入了随机对照试验(rct)和准rct,比较以中心为基础的入学准备干预与不干预、等候名单对照或正常治疗(TAU)的儿童(开始义务教育前3至7岁)。主要结果是入学准备和不良反应。资料收集和分析我们采用Cochrane期望的标准方法程序。我们使用GRADE来评估证据的确定性。我们纳入了32项试验的数据,涉及16,899名儿童(6590名儿童至少被纳入一项荟萃分析)。四项研究比较了以中心为基础的早期教育干预与无治疗控制。22项试验比较了丰富的学校课程和常规治疗(TAU)。儿童年龄在3至7岁之间(平均年龄4.4岁),51.7%为男孩,至少70%来自少数种族/民族群体。大多数研究都是在美国进行的,主要是在高度社会经济剥夺的地区。干预措施是在以中心为基础的环境中进行的(幼儿园或小学),在整个学年中,每周至少半天,每周4天。随访时间为1年(短期)、1 - 2年(中期)和2年以上(长期)。我们判断证据的确定性在所有结果测量中都是非常低到中等的。我们降低了证据的确定性,因为纳入的研究由于报告不佳、小样本量和宽置信区间引起的不精确以及统计异质性引起的不一致而存在不明确或高偏倚风险。大多数研究被认为是低风险或不明确的选择,检测,性能,损耗,选择性报告和其他偏倚。在10项研究中,分配偏倚处于高风险。美国联邦政府资助了大部分的研究。比较1。以中心为基础的早期教育干预提高入学准备与不干预的认知发展。在长期随访中,以中心为基础的早期教育干预与不干预之间的认知发展可能几乎没有差异(MD: 3.28, 95% CI: 0.23至6.34;p = 0.04;2项研究,361名受试者;低确定性证据)。情感健康和社会能力。在短期随访中,以中心为基础的早期教育干预组与无干预对照组相比,在社交技能方面可能没有明显差异(SMD: - 0.11, 95% CI: - 0.54至0.33;p = 0.63;3项研究,632名参与者;低确定性证据)。该结果的异质性很大(I²= 71%)。健康发展。一项研究的叙述性分析表明,以中心为基础的早期教育干预措施可能改善健康发展结果,如健康检查、免疫接种依从性和牙科保健(1项研究,142名参与者;低确定性证据)。 没有一项研究报告了入学准备、不良影响或身体发育。比较2。以中心为基础的早期教育干预提高入学准备与TAU的入学准备。与TAU相比,以中心为基础的早期教育干预对干预后1年入学准备的影响的证据非常不确定(SMD: 1.17, 95% CI: - 0.61至2.95;p = 0.20;2项研究,374名受试者;非常低确定性证据)。该结果的异质性相当大(I²= 95%)。认知发展。在长期随访中,以中心为基础的早期教育干预和TAU对认知发展的影响的证据非常不确定(MD: 9.34, 95% CI: - 6.64至25.32;p = 0.25;2项研究,136名受试者;非常低确定性证据)。该结果的异质性相当大(I²= 92%)。情感健康和社会能力。对12项研究的荟萃分析表明,在短期随访中,以中心为基础的早期教育干预和TAU在社交技能方面可能几乎没有差异(SMD: 0.11, 95% CI: - 0.05至0.28;p = 0.19;12项研究,4806名受试者;低确定性证据)。物理的发展。一项研究的证据表明,在短期随访中,与TAU相比,以中心为基础的早期教育干预在提高精细运动技能方面可能几乎没有差异(MD: 0.80, 95% CI: - 1.11至2.71;1项研究,334名参与者;中等确定性证据)。没有一项研究测量了不良影响或健康发展。作者的结论:我们发现非常低、低和中等确定性的证据表明,与不干预或TAU相比,以中心为基础的干预对开始上学的儿童的影响很小,甚至没有差异,持续时间长达1年。需要在美国以外进行更多的研究,衡量相关结果,以改进旨在满足儿童入学需求的项目。

Background

Globally, children are legally obliged to attend school at a certain age (ranging from 4 to 7 years old). Developmental differences are rarely considered at school entry nor are they always reflected in the teaching and learning environment. Children who start school without being ready to cope may be significantly disadvantaged. Failure at school can impact directly on long-term outcomes such as unemployment, crime, adolescent pregnancy, and psychological and physical morbidity in adulthood. In contrast, experiencing success at school can impact positively on a child's self esteem, behaviour, attitude, and future outcomes. School readiness interventions aim to prepare a child for the academic content of education and the psychosocial competencies considered important for learning such as self-regulation, listening, following instructions and learning to share in play and other social settings. There is a need for evidence of the effectiveness of centre-based school readiness interventions.

Objectives

To evaluate the effectiveness of centre-based interventions for improving school readiness in preschool children.

Search Methods

In October 2021 we searched CENTRAL, MEDLINE, Embase, ERIC, PsycINFO, ERIC, eight additional databases and three trials registers. Other eligible studies were identified through handsearches of reference lists, reports, reviews and relevant websites.

Selection Criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-RCTs comparing centre-based school readiness interventions to no intervention, wait-list control or treatment as usual (TAU) for children (aged three to 7 years before starting compulsory education). The primary outcomes were school readiness and adverse effects.

Data Collection and Analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by Cochrane. We used GRADE to assess the certainty of evidence.

Main Results

We included data from 32 trials involving 16,899 children (6590 included in at least one meta-analysis). Four studies compared centre-based early education interventions with no treatment controls. Twenty-two trials compared an enriched school curriculum to treatment as usual (TAU). Children were aged between 3 and 7 years old (mean age 4.4 years), 51.7% were boys and at least 70% were from a racial/ethnic minority group. Most studies were conducted in the USA and mainly located in areas of high socioeconomic deprivation. Interventions were delivered in centre-based settings (pre-kindergarten or elementary schools), for at least one half day, 4 days per week over the academic year. Follow-up ranged from up to 1 year (short-term), 1–2 years (medium-term) and over 2 years (long-term). We judged the certainty of evidence to be very low to moderate across all outcome measures. We downgraded the certainty of the evidence because the included studies were at an unclear or high risk of bias due to poor reporting, imprecision arising from small sample sizes and wide confidence intervals, and inconsistency due to statistical heterogeneity. Most studies were considered to be low or unclear risk for selection, detection, performance, attrition, selective reporting, and other bias. Allocation bias was at high risk in 10 studies. The US federal government funded most of the studies.

Comparison 1. Centre-based early education interventions for improving school readiness versus no intervention

Cognitive development. There may be little to no difference in cognitive development between centre-based early education interventions and no intervention at long-term follow-up (MD: 3.28, 95% CI: 0.23 to 6.34; p = 0.04; 2 studies, 361 participants; low certainty evidence).

Emotional well-being and social competence. There may be no clear difference in social skills in centre-based early education interventions compared to the no intervention control group at short-term follow-up (SMD: −0.11, 95% CI: −0.54 to 0.33; p = 0.63; 3 studies, 632 participants; low certainty evidence). Heterogeneity for this outcome was substantial (I² = 71%).

Health development. Narrative analysis from a single study showed that centre-based early education interventions may improve health development outcomes such as health checks, immunisation compliance and dental care (1 study, 142 participants; low certainty evidence).

None of the studies reported on school readiness, adverse effects, or physical development.

Comparison 2. Centre-based early education interventions for improving school readiness versus TAU

School readiness. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect of centre-based early education interventions compared to TAU on school readiness up to 1 year post-intervention (SMD: 1.17, 95% CI: −0.61 to 2.95; p = 0.20; 2 studies, 374 participants; very low certainty evidence). Heterogeneity for this outcome was considerable (I² = 95%).

Cognitive development. The evidence is very uncertain about the effect on cognitive development between centre-based early education interventions and TAU at long-term follow-up (MD: 9.34, 95% CI: −6.64 to 25.32; p = 0.25; 2 studies, 136 participants; very low certainty evidence). Heterogeneity for this outcome was considerable (I² = 92%).

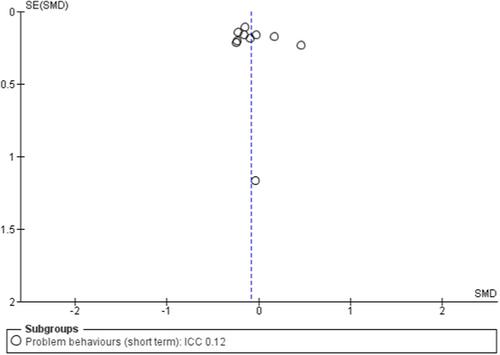

Emotional well-being and social competence. A meta-analysis of 12 studies demonstrated there may be little to no difference in social skills between centre-based early education interventions and TAU at short-term follow-up (SMD: 0.11, 95% CI: −0.05 to 0.28; p = 0.19; 12 studies, 4806 participants; low certainty evidence).

Physical development. Evidence from one study showed that centre-based early education interventions likely have little to no difference in increasing fine motor skills compared to TAU at short-term follow-up (MD: 0.80, 95% CI: −1.11 to 2.71; 1 study, 334 participants; moderate certainty evidence).

None of the studies measured adverse effects or health development.

Authors' Conclusions

We found very low, low and moderate-certainty evidence that centre-based interventions convey little to no difference to children starting school compared to no intervention or TAU, up to 1 year. More research, measuring relevant outcomes, conducted outside the USA, is required to improve programmes designed to meet the needs of children starting school.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: