有行为问题的青少年家庭(11-18岁)的功能家庭治疗:一项系统回顾和荟萃分析

摘要

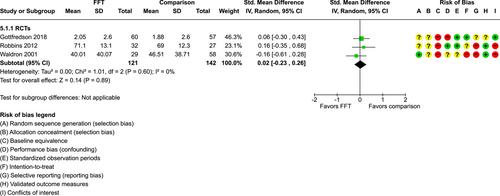

背景:功能性家庭治疗(FFT)是一种针对有行为问题的青少年的短期家庭干预。FFT在美国和其他高收入国家得到了广泛的应用。它通常被描述为一个以证据为基础的项目,具有持续的、积极的效果。我们旨在综合现有的最佳数据,以评估FFT对有行为问题的青少年家庭的有效性。检索时间为2013-2014年和2020年8月。我们检索了22个书目数据库(包括PsycINFO、ERIC、MEDLINE、Science Direct、Sociological Abstracts、Social Services Abstracts、World CAT博士论文和论文、Web of Science核心馆藏)、政府政策数据库和专业网站。查阅了文章的参考书目,并联系了专家来寻找缺失的信息。我们纳入随机对照试验(rct)和准实验设计(qed),平行队列和基线组间差异的统计对照。参与者是有行为问题的11-18岁年轻人的家庭。将FFT方案与常规服务、替代治疗和不治疗进行比较。没有出版、地理或语言的限制。两名审稿人独立筛选了1039个标题和摘要,阅读了所有可用的研究报告,评估了研究资格,并将数据提取到结构化的电子表格中。我们使用改进版的Cochrane ROB工具和What Works Clearinghouse标准来评估偏倚风险(ROB)。在可能的情况下,我们使用具有逆方差权重的随机效应模型来汇总研究结果。我们对二分类结果使用比值比,对连续结果使用标准化平均差异。我们使用对冲来调整小样本量。采用χ2和I2评价效果的异质性。我们为概念上不同的结果和不同的终点(转诊后9、9 - 14、15-23和24-42个月)制作了单独的森林图。我们根据研究设计(RCT或QED)对研究进行分组,然后用χ2检验评估这两个亚组研究之间的差异。我们使用相关效应(CE)模型和小样本校正来合成所有可用的结果数据,生成了稳健的方差估计。探索性CE分析评估了这些领域内影响的潜在调节因子。我们使用GRADE指南评估转诊后1年6个主要结局的证据确定性。20项研究(14项rct和6项qed)符合我们的纳入标准。其中15项研究为meta分析提供了有效数据;这些研究包括相关FFT组和对照组的10,980个家庭。所有纳入的研究在至少一个指标上存在高偏倚风险。一半的研究在基线等效性、支持意向治疗分析、选择性报告和利益冲突方面存在高偏倚风险。15项研究的结果和终点报告不完整。使用GRADE分类,我们发现FFT的证据的确定性对于我们所有的主要结局都非常低。使用两两荟萃分析,我们发现没有证据表明FFT与其他积极治疗相比对任何主要或次要结局有影响。主要结果是:再犯、家庭外安置、内化行为问题、外部行为问题、自我报告的犯罪和吸毒或酗酒。次要结果是:同伴关系和亲社会行为、青少年自尊、父母症状和行为、家庭功能、学校出勤率和学校表现。两两荟萃分析的研究很少(k < 7),而且在大多数分析中,研究间的效应几乎没有异质性。rct和qed的效果估计几乎没有差异。更全面的CE模型显示FFT在某些领域有积极结果,而在其他领域有消极结果,但这些影响很小(标准化平均差[SMD] 0.20|),与没有影响没有显著差异,只有一个例外:两项研究发现FFT对青少年药物滥用有积极影响,两项研究发现该领域无结果,该结果的总体效果估计在统计学上与零不同。 在所有结果(15项研究和293个效应大小)中,检测到小的积极效应(SMD = 0.19, SE = 0.09),但这些与零效应没有显著差异。预测区间表明,未来FFT评估可能产生广泛的结果,包括适度的负面影响和强烈的正面结果(- 0.37至0.75)。10项随机对照试验和5项qed的结果表明,FFT对有行为问题的青少年及其家庭并没有产生一致的益处或危害。结果的积极或消极方向在研究内部和研究之间是不一致的。大多数结果没有完全报告,现有证据的质量是次优的,证据的确定性非常低。由于选择性报道和出版偏差,FFT效果的总体估计可能会被夸大。

Background

Functional Family Therapy (FFT) is a short-term family-based intervention for youth with behaviour problems. FFT has been widely implemented in the USA and other high-income countries. It is often described as an evidence-based program with consistent, positive effects.

Objectives

We aimed to synthesise the best available data to assess the effectiveness of FFT for families of youth with behaviour problems.

Search Methods

Searches were performed in 2013–2014 and August 2020. We searched 22 bibliographic databases (including PsycINFO, ERIC, MEDLINE, Science Direct, Sociological Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, World CAT dissertations and theses, and the Web of Science Core Collection), as well as government policy databanks and professional websites. Reference lists of articles were examined, and experts were contacted to search for missing information.

Selection Criteria

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-experimental designs (QEDs) with parallel cohorts and statistical controls for between-group differences at baseline. Participants were families of young people aged 11–18 with behaviour problems. FFT programmes were compared with usual services, alternative treatment, and no treatment. There were no publication, geographic, or language restrictions.

Data Collection and Analysis

Two reviewers independently screened 1039 titles and abstracts, read all available study reports, assessed study eligibility, and extracted data onto structured electronic forms. We assessed risks of bias (ROB) using modified versions of the Cochrane ROB tool and the What Works Clearinghouse standards. Where possible, we used random effects models with inverse variance weights to pool results across studies. We used odds ratios for dichotomous outcomes and standardised mean differences for continuous outcomes. We used Hedges g to adjust for small sample sizes. We assessed the heterogeneity of effects with χ2 and I2. We produced separate forest plots for conceptually distinct outcomes and for different endpoints (<9, 9–14, 15–23, and 24–42 months after referral). We grouped studies by study design (RCT or QED), and then assessed differences between these two subgroups of studies with χ2 tests. We generated robust variance estimates, using correlated effects (CE) models with small sample corrections to synthesise all available outcome data. Exploratory CE analyses assessed potential moderators of effects within these domains. We used GRADE guidelines to assess the certainty of evidence on six primary outcomes at 1 year after referral.

Main Results

Twenty studies (14 RCTs and 6 QEDs) met our inclusion criteria. Fifteen of these studies provided some valid data for meta-analysis; these studies included 10,980 families in relevant FFT and comparison groups. All included studies had high risks of bias on at least one indicator. Half of the studies had high risks of bias on baseline equivalence, support for intent-to-treat analysis, selective reporting, and conflicts of interest. Fifteen studies had incomplete reporting of outcomes and endpoints. Using the GRADE rubric, we found that the certainty of evidence for FFT was very low for all of our primary outcomes. Using pairwise meta-analysis, we found no evidence of effects of FFT compared with other active treatments on any primary or secondary outcomes. Primary outcomes were: recidivism, out-of-home placement, internalising behaviour problems, external behaviour problems, self-reported delinquency, and drug or alcohol use. Secondary outcomes were: peer relations and prosocial behaviour, youth self esteem, parent symptoms and behaviour, family functioning, school attendance, and school performance. There were few studies in the pairwise meta-analysis (k < 7) and little heterogeneity of effects across studies in most of these analyses. There were few differences between effect estimates obtained in RCTs versus QEDs. More comprehensive CE models showed positive results of FFT in some domains and negative results in others, but these effects were small (standardised mean difference [SMD] <|0.20|) and not significantly different from no effect with one exception: Two studies found positive effects of FFT on youth substance abuse and two studies found null results in this domain, and the overall effect estimate for this outcome was statistically different from zero. Over all outcomes (15 studies and 293 effect sizes), small positive effects were detected (SMD = 0.19, SE = 0.09), but these were not significantly different from zero effect. Prediction intervals showed that future FFT evaluations are likely to produce a wide range of results, including moderate negative effects and strong positive results (−0.37 to 0.75).

Authors’ Conclusions

Results of 10 RCTs and five QEDs show that FFT does not produce consistent benefits or harms for youth with behavioural problems and their families. The positive or negative direction of results is inconsistent within and across studies. Most outcomes are not fully reported, the quality of available evidence is suboptimal, and the certainty of this evidence is very low. Overall estimates of effects of FFT may be inflated, due to selective reporting and publication biases.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: