Predicting and projecting memory: Error and bias in metacognitive judgements underlying testimony evaluation

Abstract

Purpose

Metacognitive judgements of what another person would remember had they experienced a stimulus—that is social metamemory judgements, are likely to be important in evaluations of testimony in criminal and civil justice systems. This paper develops and tests predictions about two sources of error in social metamemory judgements that have the potential to be important in legal contexts—errors resulting from beliefs informed by own memory being inappropriately applied to the memory of others, and errors resulting from differential experience of an underlying stimulus.

Method

We examined social metamemory judgements in two experimental studies. In Experiment 1 (N = 323), participants were required to make either social metamemory judgements relating to faces or predictions relating to their own memory for faces. In Experiment 2 (N = 275), we manipulated participant experience of faces, holding the described experience of the person whose memory was being assessed constant and asked participants to make social metamemory judgements.

Results

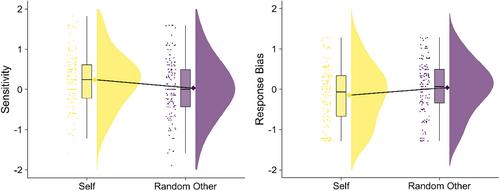

As predicted, judgements relating to the memory of others were prone to inaccuracy. Whilst participants making predictions relating to their own memory performed above chance, participants making social metamemory judgements performed no better than chance. Social metamemory judgements were also influenced by the way stimuli were experienced by an assessor, even where this experience did not correspond to the experience of the person whose memory they were assessing.

Conclusions

Having our own experiences of memory does not necessarily make us well-placed to assess the memory of others, and, in fact, our own experiences of memory can even be misleading in making judgements about the memory of others.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: