What is the effect of intergenerational activities on the wellbeing and mental health of children and young people?: A systematic review

Abstract

Background

Societal changes have led to greater isolation and higher levels of loneliness particularly for older generations. Loneliness is a significant public health challenge leading to increased levels of poor mental health. Depression and anxiety are also increasing in prevalence amongst children and young people. Intergenerational activities are interventions designed to bring together older and younger generations with the purpose of allowing participants to utilise their experiences and skills, and to give participants a chance to experience the pleasure and excitement that occurs with the transmission of knowledge and skills from one generation to another. Intergenerational activities are therefore potential interventions that can address the growing problems associated with loneliness and lack of wellbeing.

Objectives

This systematic review aims to examine the impact of intergenerational interventions on the wellbeing and mental health in children and adolescents, and potential harmful effects. It also aims to identify areas for future research as well as key messages for service commissioners.

Search Methods

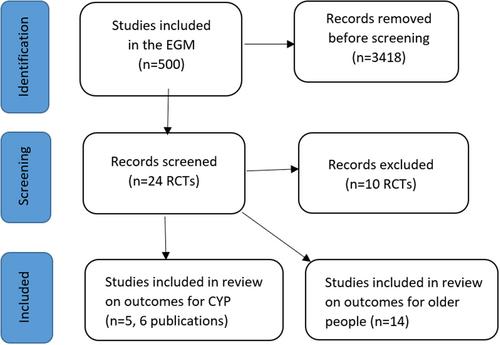

We searched an evidence and gap map published in 2022 (comprehensive searches conducted July 2021 and updated June 2023) to identify randomised controlled trials of intergenerational interventions that report mental health and wellbeing outcomes for children and young people.

Selection Criteria

Randomised controlled trials of intergenerational interventions that involved unrelated younger and older people with at least one skipped generation between them and reported mental health or wellbeing outcomes for children and young people were included in this review.

Data Collection and Analysis

We used standard methodological procedures expected by The Campbell Collaboration. We conducted data extraction and Cochrane risk of bias assessments in EPPI reviewer.

Main Results

While we identified 500 evaluations of intergenerational interventions, where the impact on participating children and/or young people was evaluated this was most often limited to assessing their impact on attitudes to aging. We identified five studies evaluating five different types of intergenerational interventions which included one-off sessions to ones that spanned a year measuring their impact on the mental health and wellbeing of children and/or young people. The purposes of the interventions differed, which included promoting social skills, preventing harmful behaviour and promoting learning. The ages of children also varied across the five studies, with one targeting younger children, two targeting younger teenagers and two targeting older teenagers. One study included socioeconomically disadvantaged children, and in the other studies the socioeconomic backgrounds of the children and young people were not described. The outcome measures used to evaluate the interventions varied with none of the studies measuring the same outcomes. One study showed improvements in wellbeing measures, and this was an intervention delivered to children in deprived neighbourhoods, where the intervention duration was for a year allowing the development of a greater depth of relationship between the younger and older participants. Four studies found no……. The included studies were at high risk of bias therefore raising uncertainty in the reliability of the findings. Underpinning theories that supported the development of the interventions and explained the mechanisms of effect were poorly described.

Authors' Conclusions

The evidence for the effectiveness of intergenerational interventions on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people is limited and inconclusive. Few evaluations have sought to measure how intergenerational interventions impact children and young people and where this impact is measured the focus is usually limited to attitudes to aging. The evidence that has been collected is too heterogenous to allow synthesis of the findings. The underpinning theories to support their development are poorly described with no follow-up data to ascertain if benefits are maintained. Intergenerational interventions show promise but researchers have failed to measure how they impact on the mental health and wellbeing of children and young people. This is a serious limitation of the evidence base that needs to be addressed in robust and rigorous evaluations.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: