PRIORITI: Phase 4 study of triptorelin or active surveillance in high-risk prostate cancer

Abstract

Aim

To evaluate the efficacy and safety of triptorelin after radical prostatectomy (RP) in patients with negative lymph nodes.

Methods

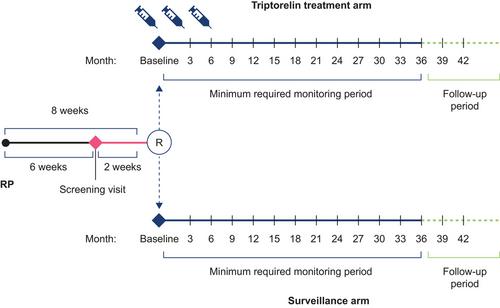

PRIORITI (NCT01753297) was a prospective, open-label, randomized, controlled, phase 4 study conducted in China and Russia. Patients with high-risk (Gleason score ≥ 8 and/or pre-RP prostate-specific antigen [PSA] ≥ 20 ng/mL and/or primary tumor stage 3a) prostate adenocarcinoma without evidence of lymph node or distant metastases were randomized to receive triptorelin 11.25 mg at baseline (≤ 8 weeks after RP) and at 3 and 6 months, or active surveillance. The primary endpoint was biochemical relapse-free survival (BRFS), defined as the time from randomization to biochemical relapse (BR; increased PSA > 0.2 ng/mL). Patients were monitored every 3 months for at least 36 months; the study ended when 61 BRs were observed.

Results

The intention-to-treat population comprised 226 patients (mean [standard deviation] age, 65.3 [6.4] years), of whom 109 and 117 were randomized to triptorelin or surveillance, respectively. The median BRFS was not reached. The 25th percentile time to BRFS (95% confidence interval) was 39.1 (29.9–not estimated) months with triptorelin and 30.0 (18.6–42.1) months with surveillance (p = 0.16). There was evidence of a lower risk of BR with triptorelin versus surveillance but this was not statistically significant at the 5% level (p = 0.10). Chemical castration was maintained at month 9 in 93.9% of patients who had received triptorelin. Overall, triptorelin was well tolerated and had an acceptable safety profile.

Conclusion

BRFS was observed to be longer with triptorelin than surveillance, but the difference was not statistically significant.

Plain language summary

After a diagnosis of prostate cancer, one of the current treatments is surgical removal of the prostate and its cancer from the body. This is called radical prostatectomy. This may cure the person. Unfortunately, sometimes the tumor may have already spread into neighboring cells (lymph nodes). If this has happened, we know that giving people a chemical castration therapy to lower their levels of male sex hormones may reduce the risk of the cancer spreading further. This is achieved by giving people an androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), such as triptorelin (which is used in this study). What we do not yet know, and what we investigated in this study, is whether ADT can also benefit people who do not have signs that their cancer has already spread to the lymph nodes. Our study involved 226 men from China and Russia and investigated whether giving triptorelin for 9 months would lead to better outcomes compared with giving no additional treatment (active surveillance). All people in the study had radical prostatectomy but only half of them were given triptorelin in the following 8 weeks. The time frame of 8 weeks was used because this is the time needed to make sure that the surgery had gone well, and that no biological markers of cancer were still present in the person's blood (the marker is called prostate-specific antigen [PSA]). High levels of PSA are a sign that the prostate cancer has returned. People were monitored for 3 years with regular checks of their castration status and levels of the cancer marker (PSA). At the end of the study, we saw that it took longer for PSA levels to increase for people who had taken triptorelin than it did for those who had not had additional treatment, but the difference was not statistically significant. There were no unexpected safety concerns seen among the people taking triptorelin. Our findings are promising but more studies are needed to confirm if starting triptorelin shortly after surgery can benefit this group of people who have had their prostate cancer treated by radical prostatectomy and have no signs that their cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

[Correction added on 31th July 2024, after first online publication: Plain language summary is added in this version.]

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: