A global latitudinal gradient in the proportion of terrestrial vertebrate forest species

Abstract

Aim

Global patterns in species distributions such as the latitudinal biodiversity gradient are of great interest to ecologists and have been thoroughly studied. Whether such a gradient holds true for the proportion of species associated with key ecotypes such as forests is however unknown. Identifying a gradient and ascertaining the factors causing it could further our understanding of community sensitivity to deforestation and uncover drivers of habitat specialization. The null hypothesis is that proportions of forest species remain globally consistent, though we hypothesize that proportions will change with differences in ecotype amount, spatial structure, and environmental stability. Here we study whether the proportion of forest species follows a latitudinal gradient, and test hypotheses for why this may occur.

Location

Worldwide.

Time period

Present.

Major taxa studied

Terrestrial vertebrates.

Methods

We combined range maps and habitat use data for all terrestrial vertebrates to calculate the proportion of forest species in an area. We then used data on the global distribution of current, recent historical, and long-term historical forest cover, as well as maps of global disturbances and plant diversity to test our hypotheses using generalized linear models.

Results

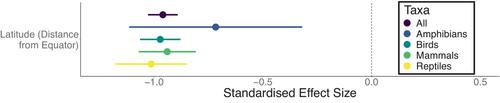

We identified a latitudinal gradient in the proportion of forest species whereby the highest proportions occurred at the equator and decreased polewards. We additionally found that the proportion of forest species increased with current forest cover, historical deforestation, plant structural complexity, and habitat stability. Despite the inclusion of these variables, the strong latitudinal gradient remained, suggesting additional causes of the gradient.

Main conclusions

Our findings suggest that the global distribution of the proportion of forest species is a result of recent ecological, as well as long-term evolutionary factors. Interestingly, high proportions of forest species were found in areas that experienced historical deforestation, suggesting a lagged response to such perturbations and potential extinction debt.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: