Geometric effects of fragmentation are likely to mitigate diversity loss following habitat destruction in real-world landscapes

Abstract

Aim

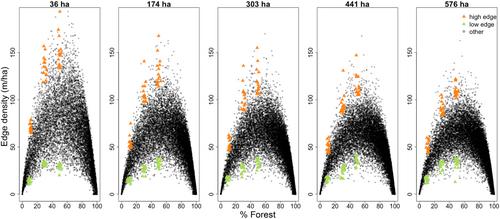

Habitat conversion is the number one threat to biodiversity. The loss of biodiversity due to habitat loss might be exacerbated if species are harmed by fragmentation per se—the breaking apart of natural habitat that remains (hereafter fragmentation). However, the evidence that species are harmed by habitat fragmentation is mixed. Studies at the patch scale tend to show that fragmentation reduces diversity due to negative demographic effects on species' dispersal, survival and fecundity. In contrast, studies at the landscape scale tend to show that fragmentation increases diversity. This discrepancy may be partly due to geometric effects, defined as greater species turnover between patches in more fragmented landscapes. Although these effects have been demonstrated theoretically and are expected to be stronger across larger spatial extents, it is unclear whether they are likely to occur in real-world settings with both realistic landscape patterns and communities. Here, we investigated the possibility of geometric effects using simulations combined with real-world landscape and community data.

Location

New Jersey, northeastern USA.

Time period

Current.

Taxa studied

Bees.

Methods

We focused on landscape sizes within the typical range for protected areas (36–576 ha), simulated forest loss using real landscape patterns, and simulated forest-bee communities based on field data we collected.

Results

We found weak but positive effects of fragmentation: immediately following forest destruction, the most fragmented forests harboured up to 7.3% more species than the least fragmented forests of the same area, in agreement with observational studies of biodiversity along fragmentation gradients. In contrast to expectations, however, the overall effects of fragmentation did not change with spatial extent.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that fragmentation can mitigate biodiversity loss immediately following habitat destruction, but that the benefits do not vary strongly with spatial extent in real-world landscapes and at extents relevant to land management.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: