The effects of flipped classrooms to improve learning outcomes in undergraduate health professional education: A systematic review

Abstract

Background

The ‘flipped classroom’ approach is an innovative approach in educational delivery systems. In a typical flipped class model, work that is typically done as homework in the didactic model is interactively undertaken in the class with the guidance of the teacher, whereas listening to a lecture or watching course-related videos is undertaken at home. The essence of a flipped classroom is that the activities carried out during traditional class time and self-study time are reversed or ‘flipped’.

Objectives

The primary objectives of this review were to assess the effectiveness of the flipped classroom intervention for undergraduate health professional students on their academic performance, and their course satisfaction.

Search Methods

We identified relevant studies by searching MEDLINE (Ovid), APA PsycINFO, Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) as well as several more electronic databases, registries, search engines, websites, and online directories. The last search update was performed in April 2022.

Selection Criteria

Included studies had to meet the following criteria: Participants: Undergraduate health professional students, regardless of the type of healthcare streams (e.g., medicine, pharmacy), duration of the learning activity, or the country of study. Intervention: We included any educational intervention that included the flipped classroom as a teaching and learning tool in undergraduate programs, regardless of the type of healthcare streams (e.g., medicine, pharmacy). We also included studies that aimed to improve student learning and/or student satisfaction if they included the flipped classroom for undergraduate students. We excluded studies on standard lectures and subsequent tutorial formats. We also excluded studies on flipped classroom methods, which did not belong to the health professional education(HPE) sector (e.g., engineering, economics). Outcomes: The included studies used primary outcomes such as academic performance as judged by final examination grades/scores or other formal assessment methods at the immediate post-test, as well as student satisfaction with the method of learning. Study design: We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-experimental studies (QES), and two-group comparison designs. Although we had planned to include cluster-level RCTs, natural experiments, and regression discontinuity designs, these were not available. We did not include qualitative research.

Data Collection and Analysis

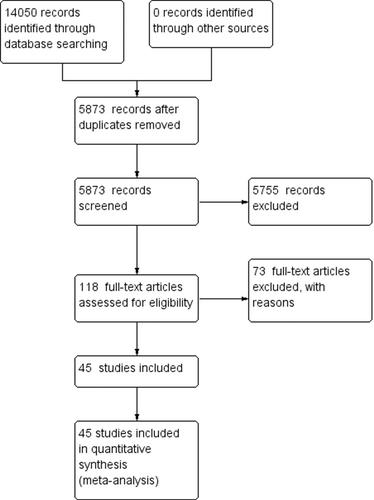

Two members of the review team independently screened the search results to assess articles for their eligibility for inclusion. The screening involved an initial screening of the title and abstracts, and subsequently, the full text of selected articles. Discrepancies between the two investigators were settled through discussion or consultation with a third author. Two members of the review team then extracted the descriptions and data from the included studies.

Main Results

We found 5873 potentially relevant records, of which we screened 118 of them in full text, and included 45 studies (11 RCTs, 19 QES, and 15 two-group observational studies) that met the inclusion criteria. Some studies assessed more than one outcome. We included 44 studies on academic performance and eight studies on students' satisfaction outcomes in the meta-analysis. The main reasons for excluding studies were that they had not implemented a flipped class approach or the participants were not undergraduate students in health professional education. A total of 8426 undergraduate students were included in 45 studies that were identified for this analysis. The majority of the studies were conducted by students from medical schools (53.3%, 24/45), nursing schools (17.8%, 8/45), pharmacy schools (15.6%, 7/45). medical, nursing, and dentistry schools (2.2%, 1/45), and other health professional education programs (11.1%, 5/45). Among these 45 studies identified, 16 (35.6%) were conducted in the United States, six studies in China, four studies in Taiwan, three in India, two studies each in Australia and Canada, followed by nine single studies from Brazil, German, Iran, Norway, South Korea, Spain, the United Kingdom, Saudi Arabia, and Turkey. Based on overall average effect sizes, there was better academic performance in the flipped class method of learning compared to traditional class learning (standardised mean difference [SMD] = 0.57, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 0.25 to 0.90, τ2: 1.16; I2: 98%; p < 0.00001, 44 studies, n = 7813). In a sensitivity analysis that excluded eleven studies with imputed data from the original analysis of 44 studies, academic performance in the flipped class method of learning was better than traditional class learning (SMD = 0.54, 95% CI = 0.24 to 0.85, τ2: 0.76; I2: 97%; p < 0.00001, 33 studies, n = 5924); all being low certainty of evidence. Overall, student satisfaction with flipped class learning was positive compared to traditional class learning (SMD = 0.48, 95% CI = 0.15 to 0.82, τ2: 0.19, I2:89%, p < 0.00001, 8 studies n = 1696); all being low certainty of evidence.

Authors' Conclusions

In this review, we aimed to find evidence of the flipped classroom intervention's effectiveness for undergraduate health professional students. We found only a few RCTs, and the risk of bias in the included non-randomised studies was high. Overall, implementing flipped classes may improve academic performance, and may support student satisfaction in undergraduate health professional programs. However, the certainty of evidence was low for both academic performance and students' satisfaction with the flipped method of learning compared to the traditional class learning. Future well-designed sufficiently powered RCTs with low risk of bias that report according to the CONSORT guidelines are needed.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: