重新思考测量不变性的因果关系

IF 2.2

Current research in ecological and social psychology

Pub Date : 2025-01-01

DOI:10.1016/j.cresp.2025.100241

引用次数: 0

摘要

测量不变性经常被吹捧为群体比较的必要统计先决条件。通常,当存在反对度量不变性的证据时,分析结束。在这里,我们向读者介绍测量不变性的另一种观点,将重点从统计程序转移到因果关系。从这个角度来看,对测量不变性的违反意味着在组之间的测量过程中存在潜在的有趣的差异,这可以保证对它们自己的权利进行解释。我们用假设的有意义的违反度量、标量和剩余不变性的例子来说明这一点。与此同时,测试测量不变性的标准程序依赖于对数据生成过程强有力的因果假设,而在其他情况下,研究人员往往不愿认可这些假设。我们指出了两条截然不同的前进道路。首先,对于想要致力于潜在因素模型的研究人员来说,可以对违反测量不变性的行为进行后续调查,调查这些行为发生的原因,将它们从死胡同变成新的研究问题。其次,对于那些对潜在因素模型感到更矛盾的研究人员来说,可以考虑替代方案,并且无论如何,总和分数和项目分数的组差异都可以作为有趣的描述性发现进行报道-但他们应该随后讨论各种解释,考虑到它们的合理性。本文章由计算机程序翻译,如有差异,请以英文原文为准。

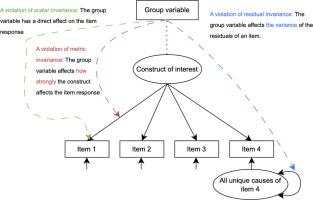

Rethinking measurement invariance causally

Measurement invariance is often touted as a necessary statistical prerequisite for group comparisons. Typically, when there is evidence against measurement invariance, the analysis ends. Here, we introduce readers to an alternative perspective on measurement invariance that shifts the focus from statistical procedures to causality. From that angle, violations of measurement invariance imply that there are potentially interesting differences in the measurement process between the groups, which could warrant explanations in their own right. We illustrate this with hypothetical examples of substantively meaningful violations of metric, scalar, and residual invariance. At the same time, standard procedures to test for measurement invariance rest on strong causal assumptions about the data-generating process that researchers may often be unwilling to endorse in other contexts. We point out two very different ways forward. First, for researchers who want to commit to latent factor models, violations of measurement invariance can be followed up with investigations into why those violations occur, turning them from a dead end into new research questions. Second, for researchers who feel more ambivalent about latent factor models, alternatives may be considered, and group differences on sum scores and item scores may be reported anyway as interesting descriptive findings—but they should be followed up with discussions of various explanations that take into account their plausibility.

求助全文

通过发布文献求助,成功后即可免费获取论文全文。

去求助

来源期刊

Current research in ecological and social psychology

Social Psychology

CiteScore

1.70

自引率

0.00%

发文量

0

审稿时长

140 days

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: