As expected, based on rapamycin-like p53-mediated gerosuppression, mTOR inhibition acts as a checkpoint in p53-mediated tumor suppression.

引用次数: 0

Abstract

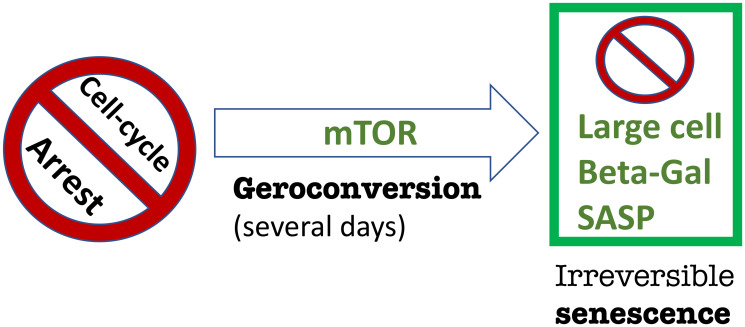

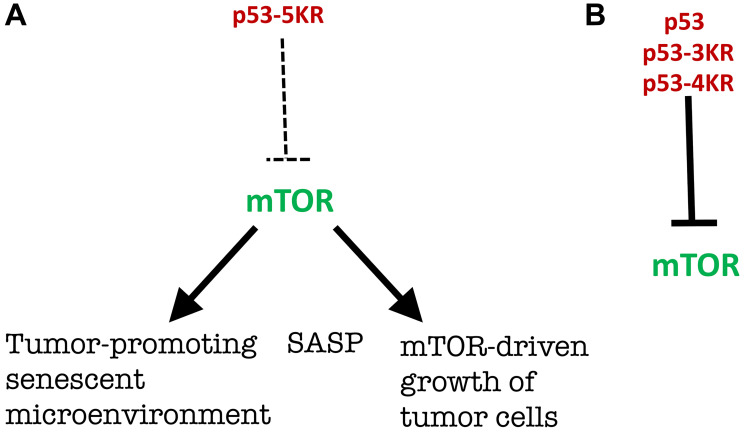

Recent work by Gu and co-workers (Kon et al., published in 2021), entitled “mTOR inhibition acts as an unexpected checkpoint in p53-mediated tumor suppression”, seemingly “unexpectedly” demonstrated in mice that the ability of p53 to suppress mTOR is essential for tumor suppression early in life [1]. This actually was predicted in 2012 in the commentary entitled “Tumor suppression by p53 without apoptosis and senescence: conundrum or rapalog-like gerosuppression?” [2] [Note: rapalogs are rapamycin analogs]. The commentary [2] was written on another fascinating paper by the same senior author Gu and co-workers (Li et al.) “Tumor suppression in the absence of p53-mediated cell-cycle arrest, apoptosis, and senescence” [3]. Mutant p53 (p53-3KR), constructed by Li et al., lacking all three then-known tumor-suppressing activities, still suppressed tumors [3]. To be precise, as noticed in the commentary [2], there were only two, not three, independent tumor-suppressing activities of p53 known at that time: namely, (i) apoptosis and (ii) cell-cycle arrest/ senescence. Wild-type p53 does not directly induce the senescent phenotype; it induces cell-cycle arrest, which then converts to senescence (geroconversion) without any p53 assistance (Figure 1). When the cell cycle gets arrested by any means (by p53, p21 or anything else), the arrested cell is not yet senescent at first. It will take several days (at least) in cell culture to observe senescent phenotype, including large cell morphology, Senescence-Associated Secretory Phenotype (SASP) and beta-Gal-staining (Figure 1). Geroconversion is driven by growth-promoting pathways such as mTOR and MAPK [4]. In fact, rapamycin and anything that inhibits mTOR such as serum-starvation, contact inhibition and anoxia partially suppresses geroconversion and the senescent phenotype (see for ref. [4]). Then how does p53 causes senescence? It causes cell-cycle arrest, which, in growth-factor rich cell culture, may automatically lead to a senescent phenotype (Figure 2A). [In analogy, a key to your home seemingly has two activities unlock the door and open the door. Yet, it only unlocks the door. When the door is unlocked by the key, you (or the wind) may open the door without key. But if an altered ”mutant” key cannot unlock the door, it cannot help to open it either]. Since mutant p53 (p53-3KR) cannot cause cell-cycle arrest, it cannot cause senescence either. On another hand, Commentary

正如预期的那样,基于雷帕霉素样p53介导的衰老抑制,mTOR抑制在p53介导的肿瘤抑制中起检查点作用。

本文章由计算机程序翻译,如有差异,请以英文原文为准。

求助全文

约1分钟内获得全文

求助全文

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: