Lactate fuels the neonatal brain.

Frontiers in neuroenergetics

Pub Date : 2011-06-03

eCollection Date: 2011-01-01

DOI:10.3389/fnene.2011.00004

引用次数: 12

Abstract

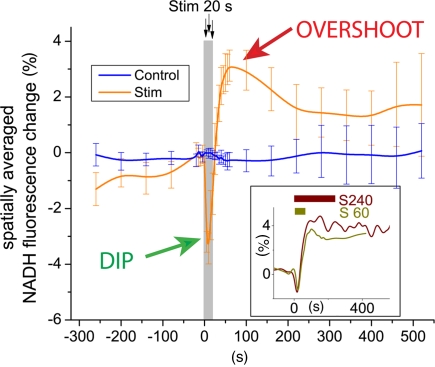

The brain is a highly oxidative organ and the prevailing dogma is that under normal conditions glucose is its principal metabolic substrate. However, it is well established that the brain is capable of oxidizing alternative substrates such as acetate, glutamate, lactate, and ketone bodies. The brain's capability to use alternative substrates may enable adaptation to extraordinary metabolic conditions such as fasting with enhanced ketogenesis or special dietary conditions during the suckling period with enhanced availability of fatty acids and ketone bodies. During early postnatal development the plasma levels of lactate, acetoacetate, and hydroxybutyrate are elevated and they replace glucose as the primary metabolic fuel until the weaning period is reached. This period is further characterized by hyperexcitability with network driven bursts of neuronal activity and calcium oscillations (Erecinska et al., 2004). Thus, glucose alone may not be sufficient to sustain the energy demands of the postnatal brain. A related question is whether alternative oxidative substrates such as lactate or hydroxybutyrate per se can sustain synaptic function in this developmental period. To address this question, Ivanov et al. (2011) simultaneously recorded oxygen tension, NAD(P)H fluorescence transients and local field potentials during electrical stimulation of the hippocampal Schaffer collateral pathway in neonatal brain tissue slices from mice. From the very beginning, the authors took great care to ensure both viability and functionality of their preparations. They convincingly demonstrated that surprisingly high superfusion rates with standard artificial cerebrospinal fluid (ACSF) in the slice chamber are required to ensure adequate oxygenation and complete electrical function in blood-free tissue slices. An important implication of this methodological tour de force is that under many previously reported experiments the requirements for viability may been met while the functionality may have been compromised. After ideal experimental conditions were established, hippocampal slices were first superfused with ACSF containing 10 mM glucose and then with modified ACSF containing 5 mM glucose and 5 mM l-lactate. Their reasoning was if glucose alone is sufficient to sustain enhanced network activity, the addition of lactate should not change tissue metabolic states and synaptic function. To the contrary, the addition of lactate significantly increased oxygen consumption (+31%) and enhanced local field potentials (+41%) during the train stimulation (10 s, 10 Hz) and radically modified the biphasic NAD(P)H signaling: the early oxidation phase was strongly augmented while the overshoot was attenuated. The authors went on to investigate whether lactate (10 mM) can sustain synaptic function in the absence of glucose as has been reported for mature brain tissue (Schurr et al., 1988). When lactate was the sole oxidative substrate, the changes were even more pronounced during a prolonged 30 s stimulus train: oxygen consumption increased by 54%, the local field potential by 39%, the oxidative phase of the NAD(P)H response was augmented threefold and the NAD(P)H overshoot essentially abolished. Furthermore, the progressive decay in the local field potential at the end of the 30-s stimulus period was less pronounced when lactate replaced glucose in the perfusate. When the experiments were repeated with the ketone body β-hydroxybutyrate (10 mM) as alternative oxidative substrate, similar effects on all measured parameters were observed. The results of the study by Ivanov et al. (2011) are clear-cut: (1) lactate, whether alone or in the presence of glucose, sustains and even augments synaptic activity and oxidative metabolism in excited neonatal brain tissue. (2) Metabolic recovery pathways are fundamentally altered when lactate or hydroxybutyrate replaces glucose as the primary oxidative substrate. The implications of this study reach beyond enhancing our understanding of how the neonatal brain functions. While the observations that lactate can serve as a substrate for the neonatal brain confirms existing knowledge, the facts that it enhances synaptic transmission and oxygen utilization are new. Furthermore, their results imply that lactate may be preferentially utilized vs. glucose, when both substrates are present at equal concentrations. This is consistent with a recent nuclear magnetic resonance study in humans that has established that lactate from the blood plasma contributes to brain metabolism both under resting and activated conditions and that the majority of plasma lactate is metabolized in neurons similar to glucose (Boumezbeur et al., 2010). An exciting question is where does the extracellular lactate originate from? Astrocytes (Pellerin and Magistretti, 1994), neurons (Caesar et al., 2008), and the blood serum (Boumezbeur et al., 2010) have been implied and direct, quantitative data on their relative contributions to lactate net transfer into neurons are needed to ultimately prove or disprove the astrocyte–neuron lactate shuttle hypothesis (Pellerin and Magistretti, 1994). The study by Ivanov et al. (2011) also provides novel data on biphasic NAD(P)H fluorescence transients (Figure (Figure1),1), an important physiological response to neural activation that has been reproduced in many studies and that is believed to originate predominately from activity-induced concentration changes to the cellular NADH pools. As stated by Galeffi et al. (2007), there seems to be general agreement that the initial NADH decrease is the consequence of mitochondrial oxidation and occurs predominantly in neurons (Shuttleworth et al., 2003; Kasischke et al., 2004; Foster et al., 2005). In contrast, conflicting interpretations on the metabolic nature of the second phase, the NADH overshoot, have been provided. Some authors have suggested that the NADH overshoot may representing glycolysis (Lipton, 1973; Mofett and LaManna, 1978, Kasischke et al., 2004), while others have implied a rise in mitochondrial NADH as a consequence of Ca2+-induced activation of the Krebs cycle dehydrogenases (Duchen, 1992; Kann et al., 2003; Shuttleworth et al., 2003; Brennan et al., 2006). Figure 1 Focal neural activity induces a characteristic biphasic NADH transient in brain tissue. This distinct physiological response (Kasischke et al., 2004) has been reported in numerous studies using brain slice preparations from mice, rats, and toad. There ... Now, Ivanov et al. (2011) show that the biphasic NADH response is fundamentally altered when lactate or β-hydroxybutyrate replaces glucose as the principal oxidative substrate: in the early phase, NADH oxidation is augmented, while during the late phase the NADH overshoot is strongly reduced. Since the augmentation of NADH oxidation concurs with increased oxygen utilization and enhanced local field potentials, there is little doubt that the early phase reflects activity-induced activation of the respiratory chain. The observation that the NADH overshoot is abolished when lactate or β-hydroxybutyrate are metabolized in the absence of glucose is consistent with a proposed glycolytic origin of the second phase. Another possibility is that the NADH overshoot is the consequence of tissue oxygen depletion during sustained activity, a condition that would be favored by low ACSF perfusion rates. As a final point, the contribution of the glial compartment to the NADH transients is uncertain (Kasischke et al., 2004; Shuttleworth, 2010). What is the way out of this conundrum? Novel experimental data is always a good answer. The biological and technical tools are readily available. For example, the experiments described by Ivanov could be repeated in hippocampal slices or in the cortex in vivo using transgenic mice with yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) targeted to neuronal mitochondria (Misgeld et al., 2007) and astrocyte-specific labeling with the red fluorescence dye sulforhodamine (Nimmerjahn et al., 2004). Under two-photon excitation the blue intrinsic NADH fluorescence could be simultaneously excited together with fluorescence from YFP and sulforhodamine, which would serve as image processing masks for neuronal mitochondria and astrocytes. While technically challenging, such imaging studies or other approaches may resolve activity-dependent metabolism in glia and neurons and shed some light on the elusive origins and sinks of extracellular lactate.

乳酸为新生儿的大脑提供能量。

本文章由计算机程序翻译,如有差异,请以英文原文为准。

求助全文

约1分钟内获得全文

求助全文

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: