Severe obesity increases risk of graft loss in pediatric heart transplantation

IF 1.9

引用次数: 0

Abstract

Objectives

Severe obesity is an established risk factor for adverse cardiovascular events and heart transplantation (HT) outcomes in adults. However, the effect of severe obesity on children after HT is not well studied. We aimed to examine the prevalence and effect of severe obesity on pediatric HT.

Methods

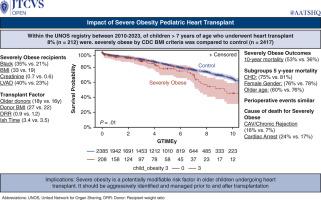

We evaluated children (>8 years) listed for HT using the United Network for Organ Sharing database. Severe obesity was defined per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention criteria using body mass index. Our study comprised 2 groups: a severe obesity group (n = 212, 8%) and a control group (n = 2417, 92%) consisting of the remaining children. We compared characteristics and outcomes between the 2 groups.

Results

After listing, there was no difference in transplant rate or waitlist mortality between the severe obesity and control groups (P = .89). Children with severe obesity were less likely to have congenital heart disease and more likely to be Black, have greater levels of creatinine, be supported with a left ventricular assist device, and receive grafts from older donors. Waitlist duration was comparable (P = .23). Incidences of primary graft dysfunction (P = .91), stroke (P = .36), dialysis (P = .18), and acute rejection (P = .4) were similar. However, severe obesity group had significant survival disadvantage (10 years: 47% vs 64%, P = .01), particularly in children older than 11 years, with diverging outcomes starting around 4 years posttransplant in those older than 15 years. Cox regression identified severe obesity as independent mortality risk factor (hazard ratio, 1.88; P = .0003), along with age, gender, race, congenital heart disease, creatinine, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and donor age.

Conclusions

There is a pressing need to improve assessment and treatment of obesity in children with end-stage heart failure awaiting transplantation. Although early survival rates are comparable, med- and long-term outcomes are concerning for severely obese children after heart transplant. Though unclear, the pathophysiologic effects are likely due to accelerated allograft vasculopathy from the metabolic derangement of obesity. Particularly in older children and adolescents, severe obesity should be considered a modifiable risk factor and aggressively managed before and after transplantation.

严重肥胖增加儿童心脏移植中移植物丢失的风险

目的:严重肥胖是成人不良心血管事件和心脏移植(HT)结果的已知危险因素。然而,重度肥胖对HT后儿童的影响还没有得到很好的研究。我们的目的是研究严重肥胖对儿童HT的患病率和影响。方法使用美国器官共享网络数据库对8岁的HT患儿进行评估。严重肥胖是根据疾病控制和预防中心使用体重指数的标准来定义的。我们的研究分为两组:重度肥胖组(n = 212, 8%)和对照组(n = 2417, 92%),由其余儿童组成。我们比较两组患者的特征和结果。结果入选后,重度肥胖组与对照组在移植率和候补死亡率方面无差异(P = 0.89)。严重肥胖的儿童患先天性心脏病的可能性更小,更有可能是黑人,肌酐水平更高,接受左心室辅助装置的支持,并接受老年供体的移植。候补名单持续时间具有可比性(P = .23)。原发性移植物功能障碍(P = 0.91)、卒中(P = 0.36)、透析(P = 0.18)和急性排斥反应(P = 0.4)的发生率相似。然而,严重肥胖组存在显著的生存劣势(10年:47% vs 64%, P = 0.01),特别是在11岁以上的儿童中,移植后4年左右开始的结果与15岁以上的儿童不同。Cox回归发现严重肥胖是独立的死亡危险因素(危险比为1.88,P = 0.0003),其他因素包括年龄、性别、种族、先天性心脏病、肌酐、体外膜氧合和供体年龄。结论迫切需要改进终末期心力衰竭等待移植儿童肥胖的评估和治疗。虽然早期存活率是相当的,但严重肥胖儿童心脏移植后的中期和长期结果令人担忧。虽然不清楚,但病理生理效应可能是由于肥胖代谢紊乱导致的同种异体移植物血管病变加速。特别是在年龄较大的儿童和青少年中,严重肥胖应被视为可改变的危险因素,并在移植前后积极管理。

本文章由计算机程序翻译,如有差异,请以英文原文为准。

求助全文

约1分钟内获得全文

求助全文

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: