Aspirational family language policy

IF 2.2

2区 文学

Q2 EDUCATION & EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH

引用次数: 0

Abstract

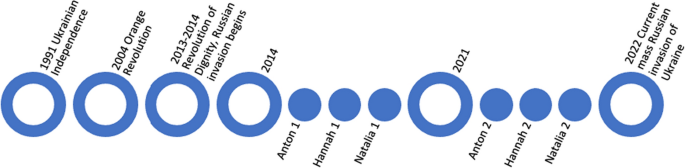

Abstract The current article applies interactional sociolinguistic discourse analysis to interviews with three parents of Ukrainian families living in New Zealand to further complexify what we know about Family Language Policy (FLP) and language transmission. More specifically, this article theorizes what we call “Aspirational FLP”—when the desired imagined language identities of family members will require families to adopt an FLP that goes above and beyond what might otherwise be considered practical. In the case of our participants, this involves Ukrainians living in the diaspora who discuss the homeland’s “changing your mother tongue” discourse (from Russian to Ukrainian) and what this means when it involves replacing one heritage language with another when both are minority languages in the hostland. Additionally, we consider the importance of both homeland and hostland sociopolitical contexts, as the interviews reflect dominant discourses from both. Finally, our interview data occurs twice with the same participants (2014 and again in 2021), therein allowing us to investigate the participants’ Aspirational FLPs diachronically, bringing further insight to the dynamism of FLP. Our findings show that participants’ Aspirational FLPs are connected to both homeland and hostland sociopolitical contexts, and as such are dynamic and shifting. Aspirational FLPs also shift differently as individual family members’ investments and imagined future identities also shift. Furthermore, the longitudinal nature of the data sheds light on how and why Aspirational FLPs become reality for some families while they remain aspirational for others. We conclude that both local contexts and wider world contexts are important to consider when investigating FLP, and diachronic research is highly valuable for uncovering factors that contribute to the complexity of FLP, both Aspirational and realized.

理想的家庭语言政策

摘要本文运用互动社会语言学的话语分析方法,对居住在新西兰的三名乌克兰家庭的父母进行访谈,以进一步丰富我们对家庭语言政策(FLP)和语言传播的了解。更具体地说,这篇文章理论化了我们所谓的“理想FLP”——当家庭成员期望的想象语言身份将要求家庭采用一种超越可能被认为是实际的FLP。就我们的参与者而言,这涉及到生活在海外的乌克兰人,他们讨论祖国的“改变你的母语”话语(从俄语到乌克兰语),以及当这涉及到用另一种传统语言取代另一种传统语言时,这意味着什么。此外,我们考虑了祖国和东道国社会政治背景的重要性,因为访谈反映了两者的主导话语。最后,我们对同一参与者进行了两次访谈(2014年和2021年),从而使我们能够历时性地调查参与者的抱负FLP,从而进一步了解FLP的动态。我们的研究结果表明,参与者的理想FLPs与祖国和东道国的社会政治背景有关,因此是动态和变化的。随着个人家庭成员的投资和想象中的未来身份的变化,理想的flp也会发生不同的变化。此外,数据的纵向性质揭示了理想的flp如何以及为什么对一些家庭成为现实,而对另一些家庭仍然是理想的。我们的结论是,在研究FLP时,当地背景和更广泛的世界背景都是重要的考虑因素,而历时研究对于揭示导致FLP复杂性的因素非常有价值,无论是期望的还是实现的。

本文章由计算机程序翻译,如有差异,请以英文原文为准。

求助全文

约1分钟内获得全文

求助全文

来源期刊

Language Policy

Multiple-

CiteScore

3.60

自引率

6.20%

发文量

35

期刊介绍:

Language Policy is highly relevant to scholars, students, specialists and policy-makers working in the fields of applied linguistics, language policy, sociolinguistics, and language teaching and learning. The journal aims to contribute to the field by publishing high-quality studies that build a sound theoretical understanding of the field of language policy and cover a range of cases, situations and regions worldwide.

A distinguishing feature of this journal is its focus on various dimensions of language educational policy. Language education policy includes decisions about which languages are to be used as a medium of instruction and/or taught in schools, as well as analysis of these policies within their social, ethnic, religious, political, cultural and economic contexts.

The journal aims to continue its tradition of bringing together solid scholarship on language policy and language education policy from around the world but also to expand its direction into new areas. The editors are very interested in papers that explore language policy not only at national levels but also at the institutional levels of schools, workplaces, families, health services, media and other entities. In particular, we welcome theoretical and empirical papers with sound qualitative or quantitative bases that critically explore how language policies are developed at local and regional levels, as well as on how they are enacted, contested and negotiated by the targets of that policy themselves. We seek papers on the above topics as they are researched and informed through interdisciplinary work within related fields such as education, anthropology, politics, linguistics, economics, law, history, ecology, and geography. We particularly are interested in papers from lesser-covered parts of the world of Africa and Asia.

Specifically we encourage papers in the following areas:

Detailed accounts of promoting and managing language (education) policy (who, what, why, and how) in local, institutional, national and global contexts.

Research papers on the development, implementation and effects of language policies, including implications for minority and majority languages, endangered languages, lingua francas and linguistic human rights;

Accounts of language policy development and implementation by governments and governmental agencies, non-governmental organizations and business enterprises, with a critical perspective (not only descriptive).

Accounts of attempts made by ethnic, religious and minority groups to establish, resist, or modify language policies (language policies ''from below'');

Theoretically and empirically informed papers addressing the enactment of language policy in public spaces, cyberspace and the broader language ecology (e.g., linguistic landscapes, sociocultural and ethnographic perspectives on language policy);

Review pieces of theory or research that contribute broadly to our understanding of language policy, including of how individual interests and practices interact with policy.

We also welcome proposals for special guest-edited thematic issues on any of the topics above, and short commentaries on topical issues in language policy or reactions to papers published in the journal.

求助内容:

求助内容: 应助结果提醒方式:

应助结果提醒方式: